Claire Bentley

READING TIME: 4 MINUTES

Content Warning // This article contains information that may be triggering for survivors of sexual violence.

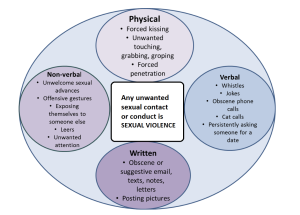

Sexual violence encompasses more than what people often think of as penetrative sex. In reality, sexual violence is any unwanted or nonconsensual sexual behaviour. For example, it includes (but is not limited to): nonconsensual touching and/or kissing, sharing intimate images of another person without their permission, sharing intimate photos with a person without their consent, and threatening or coercing someone to obtain their consent (Sexual Violence New Brunswick, 2025). Sexual violence can happen to anyone, and it can happen in any kind of relationship. For instance, this crime can occur between acquaintances, strangers, partners (being in a relationship does not automatically equal consent), ex-partners, friends, family members, coworkers, and peers.

For sexual activity to be consensual, everyone involved must give their permission.

- Given freely and enthusiastically: it does not count if someone only gives their consent because others are threatening or pressuring them. People can only give consent when they are sober and conscious.

- Ongoing: consent must be ongoing throughout the duration of the sexual activity. This requirement means that, even if someone has given consent, they can take it back. If a person takes back their consent, others must respect that decision and stop the sexual activity. If you are unsure if your partner or partners want to keep going, stop and ask.

- Specific and given for every activity: consent must be given for every new sexual activity. Just because someone gives it once for one time or activity, does not mean they consent to other behaviours or at later times. Before engaging in any sexual activity, you must ask for consent.

- Informed: for a person to give consent, they must know what they are agreeing to. This means that there must be no lies, manipulation, or tricks between everyone involved.

Talking about sexual violence is necessary because the rates of this crime are increasing in New Brunswick. According to Sexual Violence New Brunswick (2025), between 2016 and 2023, the number of survivors increased from 333 to 763, with 627 of these survivors being female, 131 males, and 5 of unknown gender. These statistics, however, must be read with caution, as sexual violence often goes unreported, and the frequency of this crime is much more prevalent than the numbers suggest.

(University of Winnipeg/Website)

Have you experienced sexual violence?

If you are a survivor of sexual violence, know that it is not your fault. Sometimes people who have experienced sexual violence think that they are at fault or that they must have done something to make it happen to them. Nothing you did made the perpetrator do this to you; it was their choice, and it is their fault. It does not matter where you were, what you were wearing, or what you were doing.

After experiencing sexual violence, there are many ways in which you may react. Fear, anger, anxiety, depression, guilt and self-blame, flashbacks, nightmares, intrusive memories, lack of trust, withdrawal, and powerlessness are all common and normal reactions. However, if you have other emotions or none at all, that is also normal. The way you feel and react is valid.

Getting medical attention

After experiencing sexual violence, it is important to seek medical attention. Even if you are not injured, there are still risks for sexually transmitted infections and pregnancy. If you go to the hospital, the staff will not report the sexual assault to the police without your permission, unless you are in immediate danger or under 19 years old. When you go to the hospital, you will see a triage nurse, and you can let them know that you would like to see a Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE). These trauma-informed nurses ask if you would like to report the assault to the police. If you decide yes, you can then choose if you would like the nurse to collect forensic evidence. If you do not want to report the assault, you can still have forensic evidence collected.

Forensic evidence kits are boxes with swabs, bags, containers, and forms to collect evidence against an experience of sexual violence. During this process, a SANE nurse or a doctor will swab your skin, genitals, mouth, and other areas for DNA. They will also collect debris or dirt on your clothes, hair, and other parts of your body. Forensic evidence kits are stored for 6 months, so if you initially decide that you do not want to report the assault to the police, you can change your mind later. In addition to completing a forensic evidence kit, SANE nurses will also check you for injuries, pregnancy, and sexually transmitted infections.

(UNBSRC/Instagram)

UNB sexual violence resources

At the University of New Brunswick Saint John, we have Campus Sexual Assault Support Advocates (CSASA) to support students who have experienced sexual violence. These advocates offer trauma-informed counselling, can help you make a report, arrange accommodations, and connect you with medical attention. CSASAs work to create a safe space for survivors so they can feel heard, believed, and validated. You can contact CSASA at csasa@svnb.ca.

The university also has a student health centre where they offer nurse practitioner and physical services. You can contact them at behealthy@unb.ca.

We also have counselling services, where you can go to talk about your experience with sexual violence or any other issue that you may be struggling with. You can contact them at sjcounsellor@unb.ca.

If you want to learn more about these services in person, the sexual violence Saint John campus advocate is holding a consent learning button and bookmark making event this Wednesday, February 11th, from 12:30-2:30 p.m. in the Whitebone Pizzeria.