On the morning of the Fall Convocation, UNBSJ was graced with the presence of Vera Schiff, a Holocaust survivor.

Schiff was born in Prague, Czechoslovakia in 1926 and was encouraged in her early life to embrace and pursue education. “Education was perceived by my parents as the most important foundation and element in a person’s life,” says Schiff. In 1942, Schiff and her family were thrown into a concentration camp in Theresienstadt, effectively ending her aspirations for a higher education.

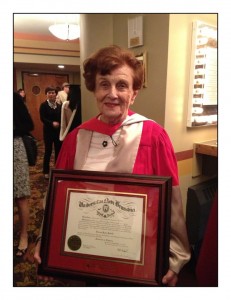

Today, many years after World War II, she is being recognized by UNBSJ with an honorary doctorate of letters for her work on educating the next generation on the horrors of the Holocaust. “I believe it imperative,” says Schiff, “for the new generation to learn what can happen when an aggressive, hateful party, with twisted objectives takes over and implements insane measures.”

Cheryl Fury, a doctor of history at UNBSJ, has been working with Schiff since 2010 when they met at the March of the Living Tour in Germany and Poland. Fury has helped Schiff revise her memoir, Theresienstadt: The Town the Nazis gave to the Jews, and her second book, Hitler‘s Inferno: Eight Personal Histories of the Holocaust. Fury has also been assisting Schiff with scholarly articles, including, Refusing to Give in to Despair: The Children and Teachers of Terezin. Fury also annotated and edited Schiff’s most recent book, The Theresienstadt Deception, which has just been released.

“Dr. Fury’s faith in me kept me inspired,” says Schiff, “and I am grateful that we have educators of her calibre. She confirms my belief that excellent educators make all the difference.”

Before receiving her doctorate of letters on the evening of Oct. 19, Schiff took the time to address students, faculty and members of the community, recounting some of her memories and experiences from the Holocaust. “Mine is a sad narrative,” says Schiff, “but these facts should serve as a warning.”

The room was full and overflowing into the hallway with people interested in hearing Schiff‘s story while she provided a narrative of Prague at the time the Nuremburg Laws were implemented by the Nazis, which restricted and removed basic human rights from the Jews.

When the Nazis invaded her hometown, Schiff recalls sneaking out of her house and the feelings that she had looking at the empty streets. “Something had died,” says Schiff, “the country had died.”

Looking out into her mesmerized audience, Schiff describes the deportation of her family and the emotions she felt as she walked away from her home. “I remember Prague seemed so beautiful, and I couldn’t understand why we were being expelled from our home when we had done nothing wrong,” says Schiff.

“Nazis were sworn to the destruction of Jews,” says Schiff, “and they were systematic about it.” She describes the whirlwind destruction and violence the Nazis brought with them to Prague, “If somebody wanted to hit me, pull my hair, beat me,” says Schiff, “no one would come to my help.”

Along with the violence came another horror Schiff emphasizes in her talk. “The hunger,” says Schiff, “the starvation. I find it hard to put into words. Hunger is a very powerful problem.”

Given a meagre diet of coffee, watery soup, and near non-existent pieces of bread, Schiff recalls dreaming about an ever elusive loaf of bread that she was never able to eat, not even in her dreams.

As she speaks, Schiff fondly and sadly remembers a Gentile and friend of her father’s, Josef Bleha, who endangered himself in order to help Schiff and her family. He saved them from boarding a transport to a death camp where they would have been killed upon arrival. Bleha also provided Schiff and her family with food while they were in the concentration camp.

“One day my father‘s friend vanished,” says Schiff. After the war she learned that he was executed for helping Jewish families, such as hers. Schiff made a case to Israel on behalf of Bleha and in 1994 he was declared Righteous among the Nations by Yad Vashem. An honour bestowed upon Gentiles who selflessly came to the aide of the Jews during the Holocaust.

Schiff expresses the hope she felt in the early years of the Holocaust, “We didn’t admit to ourselves that we didn’t have a chance,” says Schiff, “we had hope.” Eventually that hope faded and “slowly, ever so slowly we accepted the verdict.”

Schiff is the sole survivor of her 50 family members taken to concentration camps. “It was a long struggle to accept the unacceptable,” says Schiff, “and try to build on mountains of ash.”

“It is never easy to recall the darkest days of mankind that destroyed my family,” says Schiff, “but the thought that their suffering can serve as a clarion call to the young generation gives me a purpose.”

Schiff feels that her purpose in life is to educate the world on the monstrosities of Nazi rules and the Holocaust, for which she has been recognized by UNBSJ with an honorary doctorate of letters. “I am in awe that someone can live through such an awful experience and still be so full of love, compassion and tolerance,” says Fury, “I am so proud that it’s UNBSJ bestowing this honour upon her.”

Before Convocation began, Schiff wore a glowing smile as she expressed her excitement about receiving her degree. “The honour of the degree awarded to me by UNBSJ is a great recognition of my work,” says Schiff, “I am deeply grateful, and I also perceive it as respect for the millions of innocent victims, whose voices were silenced and whose memory I am trying to keep alive.”

What a wonderful article, Ocean!